ChatGPT-Induced Psychosis Isn't RealJul 29

if you’re using chatgpt to brainstorm sacrifices to bloodthirsty deities and it says some weird shit, that’s on you

Sep 23, 2025

This piece was first published on Devon’s substack.

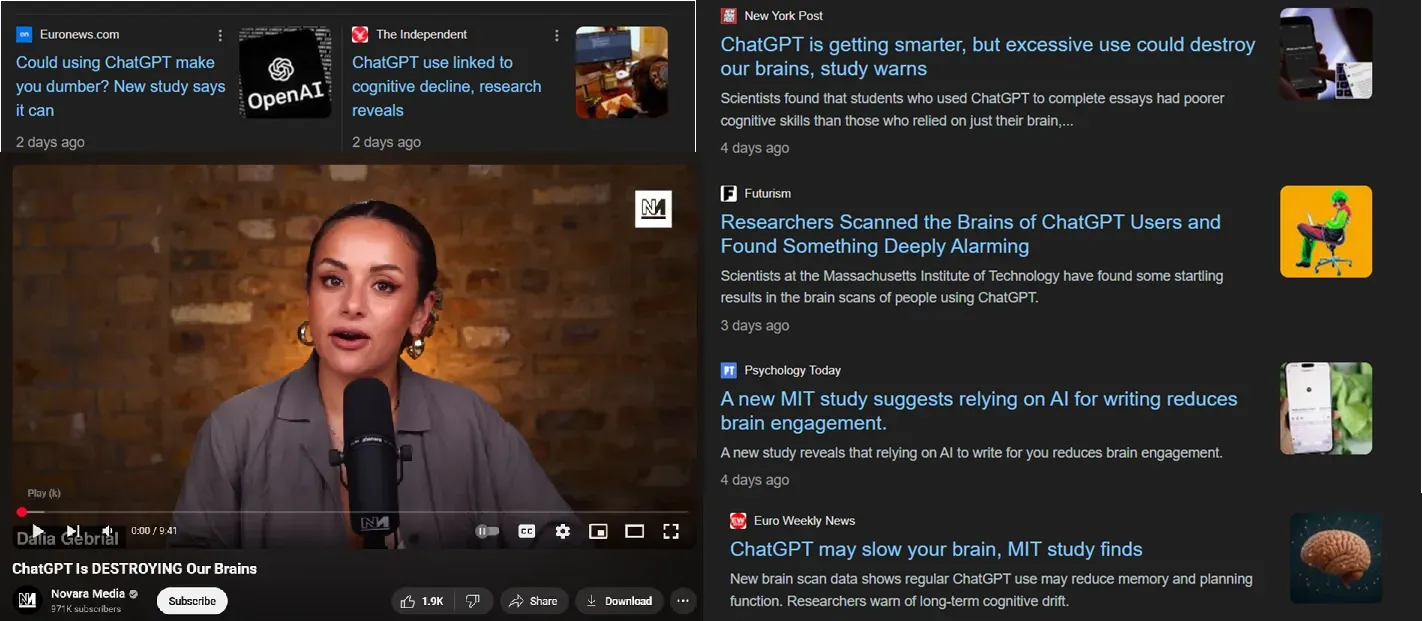

In June, an unreviewed draft of a scientific article began making the rounds, examining the relationship between LLM use and brain functionality — and since then, many reporters have incorrectly claimed it proves that using ChatGPT damages people’s brains.

As an educator and writer, I worry about programs like ChatGPT, Claude, and Google’s Gemini, which when used carelessly strip the struggle and reward out of writing. But as a psychologist and lifelong skeptic, I’m also dismayed by sloppy, sensationalistic science reporting, not to mention how eager the public is to believe any claim that sounds scary or comes paired with a grainy image of a brain scan.

So I wanted to take a moment today to unpack exactly what the study authors did, what they actually found, and what the results of their work might mean for anyone concerned about the rise of AI — or the ongoing problem of irresponsible science reporting.

This paper has not been peer-reviewed, which is generally seen as an essential part of ensuring research quality in academia.

The researchers chose to get this paper into the public eye as quickly as possible because they are concerned about the use of LLMs, so their biases and professional motivations ought to be taken into account.

Its subject pool is incredibly small (N=54 total).

Subjects had no reason to care about the quality of the essays they wrote, so it’s hardly surprising the ones who were allowed to use AI tools didn’t try.

EEG scans only monitored brain function while writing the essays, not subjects’ overall cognitive abilities or effort completing tasks they actually cared about.

Google users were also found to utilize fewer cognitive resources and engage in less memory retrieval while writing their essays, but nobody seems to hand-wring about people using search engines to augment writing anymore.

Cognitive ability and motivation were not measured in this study.

Changes in cognitive ability and motivation over time were not measured.

This was a laboratory study that cannot tell us how individuals actually use LLMs in their daily life, what the long-term effects of LLM use are, and if there are any differences in those who choose to use LLMs frequently versus those who do not.

The researchers themselves used an AI model to analyze their data.

Brain-imaging research is seductive and authoritative-seeming to the public, making it more likely to get picked up (and misrepresented) by reporters.

Educators have multiple reasons to feel professionally and emotionally threatened by widespread LLM use, which influences the studies we design and the conclusions we draw.

Students have very little reason to care about writing well right now, given the state of higher ed; if we want that to change, we have to reward slow, painstaking effort.

The stories we tell about our abilities matter. When individuals falsely believe they are “brain damaged” by using a technological tool, they will expect less of themselves and find it harder to adapt.

Head author Nataliya Kosmyna and her colleagues at the MIT Media Lab set out to study how the use of large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT affects students’ critical engagement with writing tasks, using electroencephalogram scans to monitor their brains’ electrical activity while writing. They also evaluated the quality of participants’ papers on several dimensions, and questioned them after the fact about what they remembered of their essays.